How Language Generation Works: From Tokens to Transformers

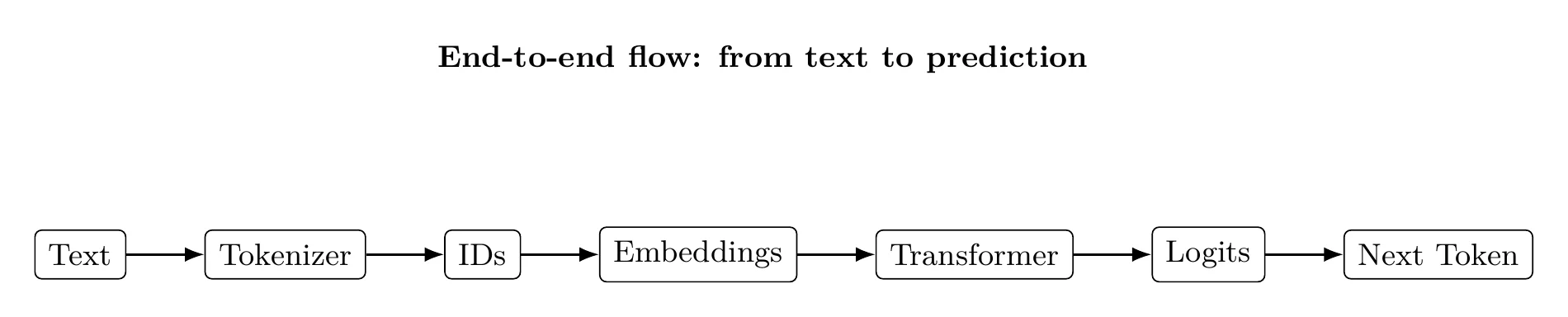

Language generation is next-token prediction over a discretized alphabet, scaled up until the inductive biases become useful. If you want to reason about what these systems can and can’t do, track the pipeline.

- Discretize text into tokens (compression + reversibility, not semantics)

- Embed token IDs into vectors (a geometry where dot-products can mean something)

- Model with attention (transformer → logits → sampling)

What matters in practice is what each stage assumes: a fixed vocabulary that covers your domain, embeddings where similarity is learnable, and attention that can exploit that geometry at scale.

What you’ll get:

- A mental model of the token → embedding → attention pipeline that’s precise enough to debug failures.

- The implicit assumptions each stage makes (and where they break).

- Concrete diagrams you can map to real model behavior.

1. Why Language Must Be Discretized

Neural networks operate on fixed-size numerical inputs, but natural language is neither fixed-size nor numerical. The first challenge, therefore, is to convert raw text into a form suitable for learning.

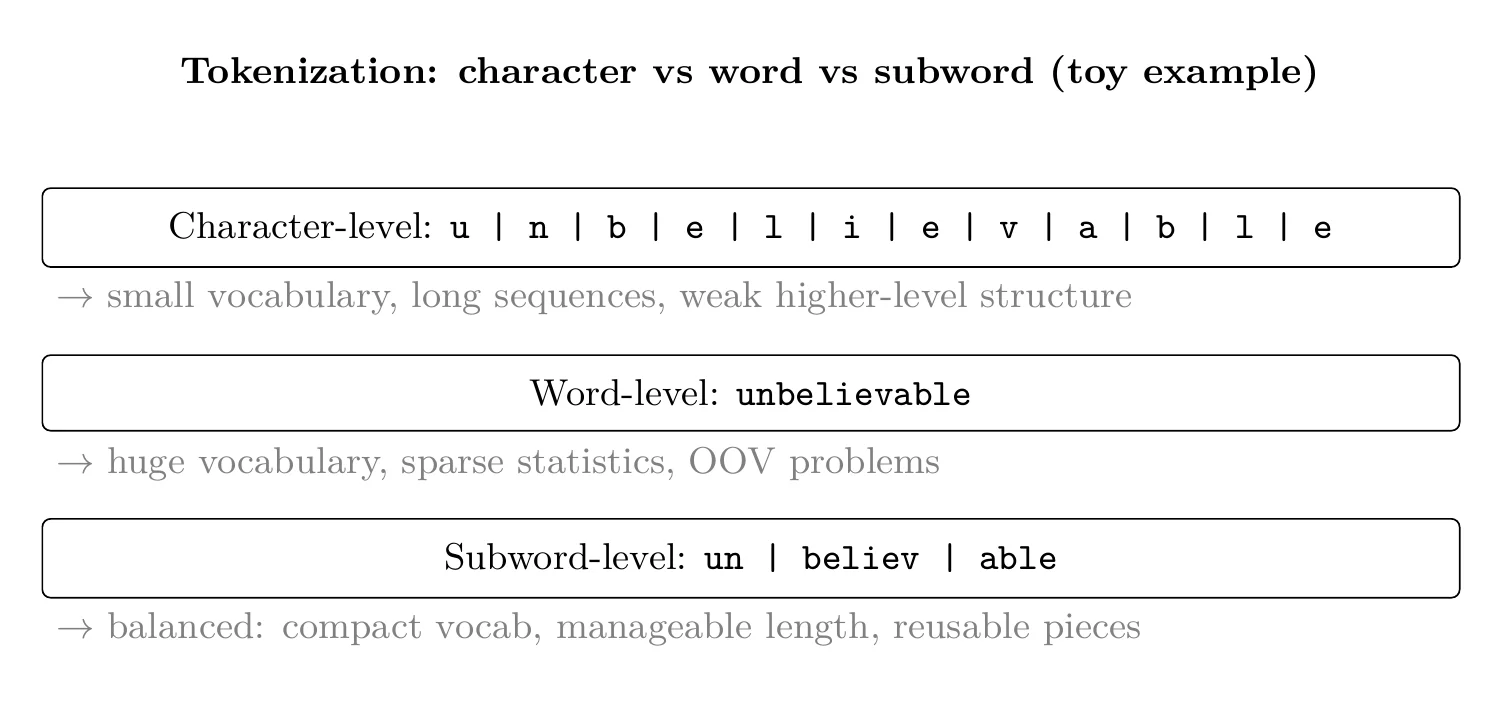

A naïve approach would be to represent each word as a one-hot vector. This immediately runs into two problems:

- Word-level vocabularies are extremely large, leading to impractically high-dimensional vectors

- Rare or unseen words cannot be represented meaningfully

At the other extreme, character-level representations avoid vocabulary explosion but lose higher-level structure. Individual characters carry very little semantic information, making learning inefficient.

The solution used by modern models lies between these extremes.

2. Tokenization as Statistical Compression

Tokenization maps raw text into a sequence of discrete symbols drawn from a fixed vocabulary. These symbols—tokens—are typically subword units: larger than characters, smaller than full words.

Importantly, tokenizers are not semantic models. They are trained to optimize statistical properties such as:

- Compactness (frequent substrings get short representations)

- Coverage (rare words can be decomposed)

- Deterministic reversibility

In practice, tokenizers are trained on large corpora to find an efficient segmentation of text that balances vocabulary size and expressiveness.

Once tokenized, text becomes a sequence of integer token IDs. These IDs are not meaningful by themselves; they are merely indices into a learned embedding table.

3. Embeddings: From Discrete Tokens to Geometry

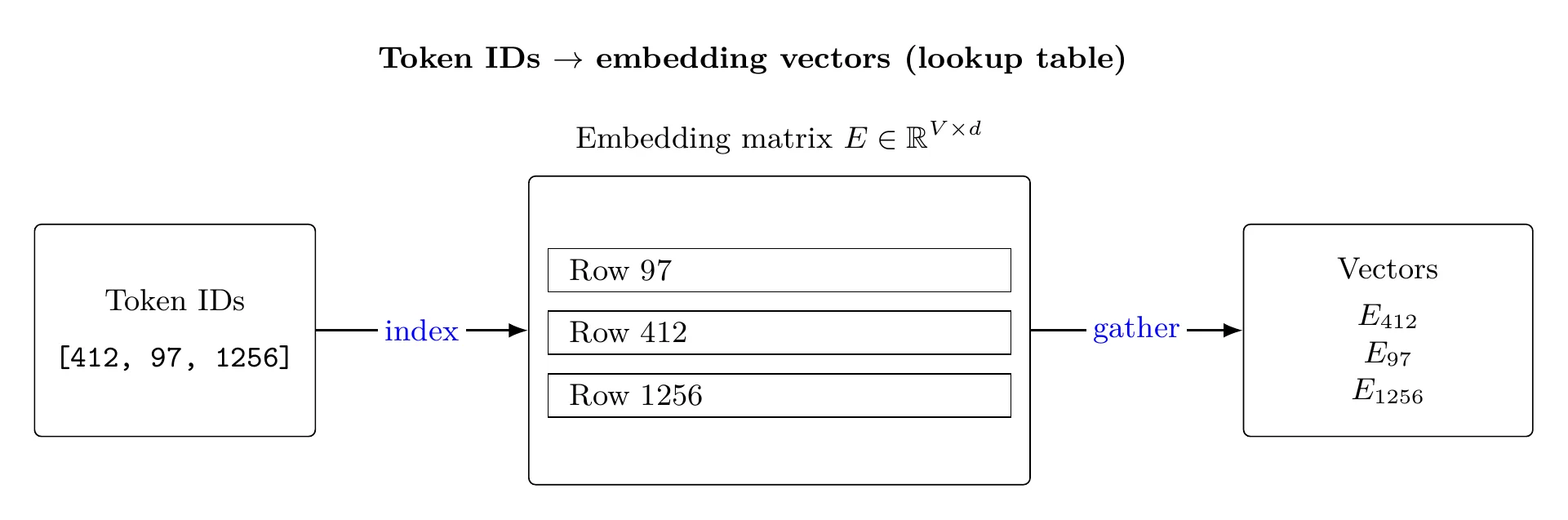

Embeddings as a Lookup Table

An embedding layer is a learned matrix , where is the vocabulary size and is the embedding dimension.

Each token ID indexes a row of this matrix, producing a dense vector. At this stage, there is nothing inherently semantic about the vectors—they are simply parameters to be optimized.

Meaning arises only through training.

---

Geometry Emerges from the Training Objective

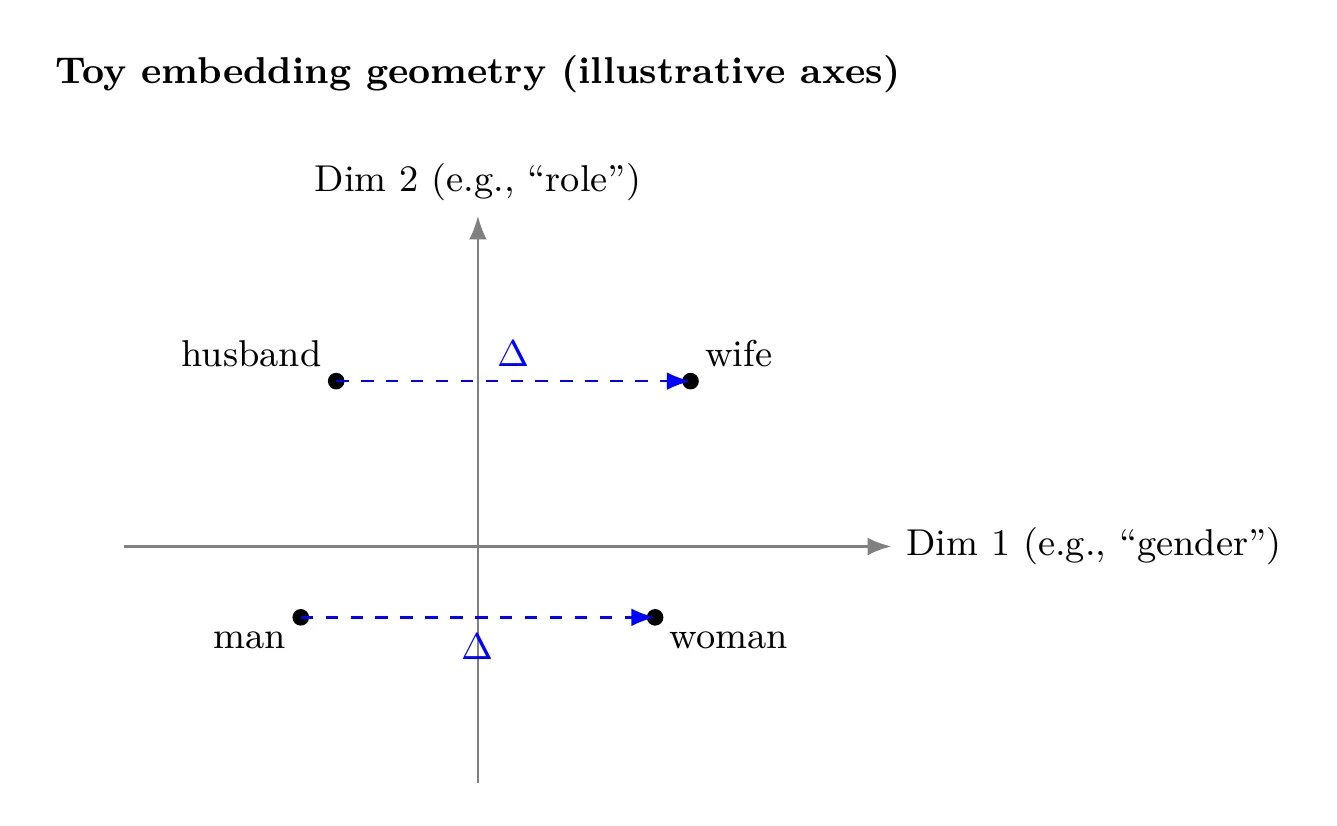

A good embedding model is one in which linguistic regularities are reflected as geometric regularities in the embedding space. This structure is not enforced directly. Instead, it emerges because the training objective rewards representations that make prediction easier.

To build intuition, consider an idealized two-dimensional embedding space:

- One axis loosely corresponds to gender

- Another corresponds to some relational or semantic role

In such a space, vectors for "man" and "woman" would differ primarily along the gender axis, while "husband" and "wife" would show a similar displacement. The important property here is not absolute position, but relative geometry—differences and directions encode relationships.

Real embedding spaces do not contain clean, interpretable axes. Instead, they are high-dimensional and distributed. Nevertheless, the same principle applies: relationships are captured through consistent geometric patterns.

This is a desired emergent property, not a guarantee. Embedding quality is ultimately empirical and is evaluated by how well geometric proximity supports generalization in downstream tasks.

4. Encoder, Decoder, and Encoder–Decoder Architectures

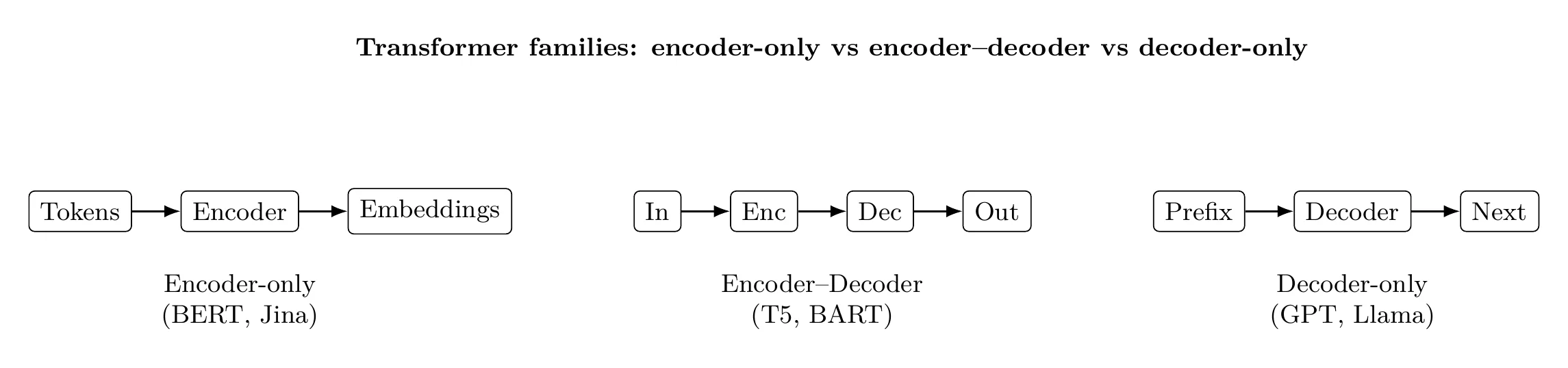

Once tokens are embedded, different model architectures determine how sequences are processed and what the model is optimized to do. Most modern language models fall into one of three categories.

Encoder-only models (e.g. Jina v3)

Encoder-only architectures process the entire input sequence simultaneously using bidirectional context. Every token can attend to every other token, allowing the model to build rich, global representations.

Embedding models such as Jina v3, developed by Jina AI, fall into this category. Their objective is not generation, but representation quality: tokens and sentences that are semantically similar should be close together in embedding space.

Because encoder-only models see full context in both directions, they are well suited for:

- Semantic search and retrieval

- Clustering and similarity comparison

- Reranking and matching tasks

They understand text in the sense of producing structured representations, but they do not generate new sequences.

Encoder–decoder models (e.g. T5)

Encoder–decoder architectures are designed for sequence-to-sequence problems. An encoder first processes the input sequence into an internal representation. A decoder then generates an output sequence conditioned on that representation.

A canonical example is T5, which frames all tasks—translation, summarization, question answering—as text-to-text transformations.

This architecture is especially effective when:

- Input and output lengths differ

- The task requires rephrasing rather than continuation

- There is a clear source → target structure

Conceptually, encoder–decoder models transform one sequence into another.

Decoder-only models (e.g. GPT-3)

Decoder-only architectures generate text autoregressively: each token is predicted conditioned only on previous tokens. There is no separate encoder; the same stack is used for both conditioning and generation.

Large language models such as GPT-3, developed by OpenAI, follow this design. Despite their simplicity, decoder-only models scale exceptionally well when trained on large corpora with next-token prediction objectives.

Their strengths include:

- Open-ended text generation

- In-context learning via prompting

- Flexible adaptation without task-specific heads

A useful way to think about the three architectures is:

- Encoders represent

- Encoder–decoders translate

- Decoders generate

The dominance of decoder-only models in modern LLMs is largely a consequence of scalability and objective alignment, not architectural expressiveness alone.

5. Transformers and the Attention Mechanism

The transformer architecture replaced recurrence with attention, enabling models to reason about all tokens in a sequence simultaneously.

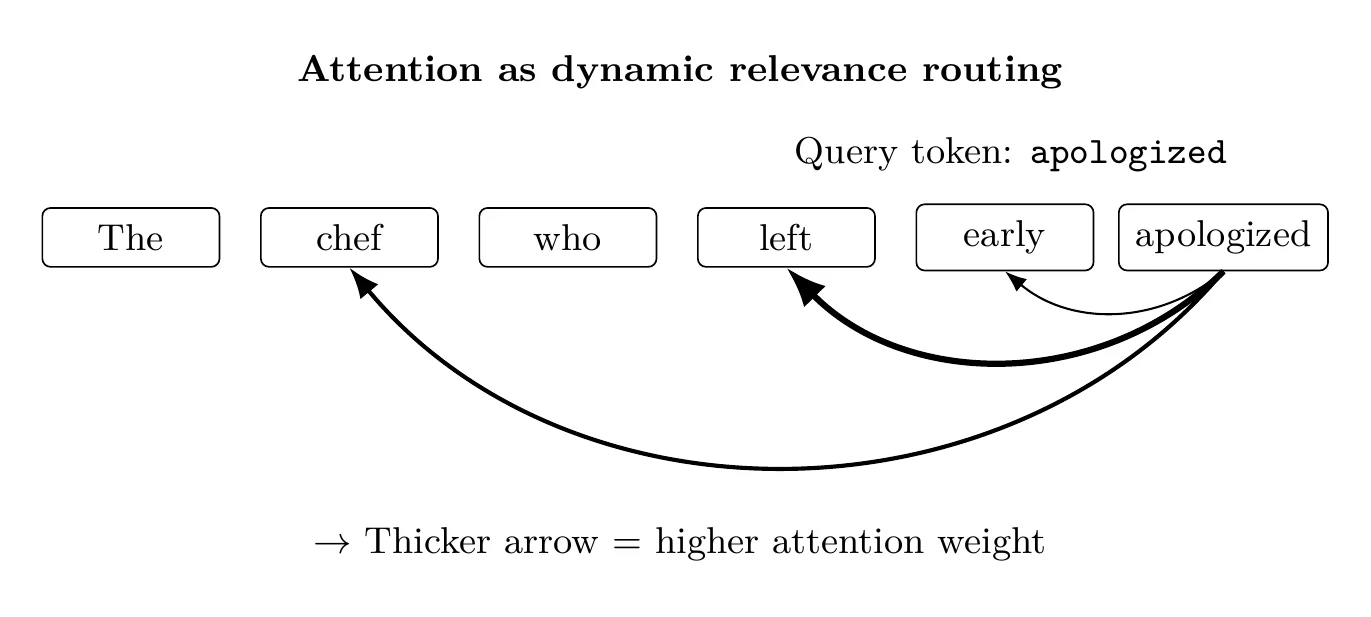

Attention allows each token to dynamically determine which other tokens are relevant to it. Rather than relying on fixed computation paths, the model computes relevance scores conditioned on the input itself.

This has several consequences:

- Long-range dependencies are handled naturally

- Computation is highly parallelizable

- Contextual relevance is learned rather than hard-coded

Multi-head attention extends this idea by allowing the model to project the same sequence into multiple relational subspaces simultaneously. Each head can specialize in different patterns—syntax, coreference, or semantic roles—while operating over the same input.

Crucially, attention assumes that dot products in embedding space are meaningful. If the embedding geometry is poor, attention has nothing useful to exploit.

6. Putting It All Together

Language generation works not because models store explicit linguistic rules, but because each component of the pipeline enforces useful inductive biases:

- Tokenization provides a compact, structured discretization of text

- Embeddings create a geometric space where similarity and relationships can be exploited

- Transformers use attention to perform conditional computation over that space

At scale, these ingredients combine to produce models that can generate coherent, context-aware text—without ever being explicitly taught grammar, syntax, or semantics.

Closing Thoughts

None of these components are individually sufficient. Tokenization without geometry is meaningless; geometry without attention is inert; attention without scale is brittle.

Language models work because all three are optimized jointly under massive data and compute. The result is not understanding in a human sense, but a highly effective statistical system that mirrors many of language's observable regularities.